![]()

![]()

|

Exhibit Guide Home Exhibits Introduction Founding Generation Founding Documents You Be the Judge Defining Freedom The Struggle Continues Faces of Freedom Marketplace of Ideas Censorship: What Is It? Musical Hit List Draw the Line Resources Museum Map Glossary |

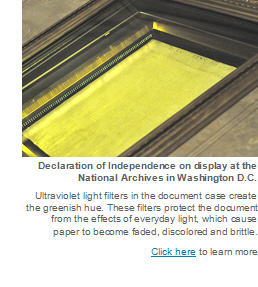

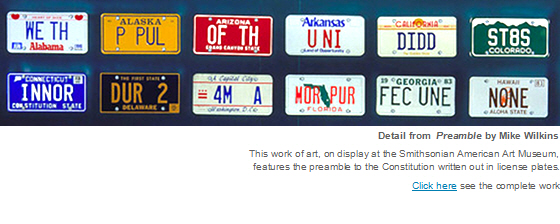

Our nation’s founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights, and Constitution—are the result of years of debate between the founders over what rights, responsibilities and government limits should be included in these papers. They grew out of a long struggle for freedom in both Europe and America. Today, the freedoms in the Constitution and Bill of Rights continue to be actively debated every day in our seats of government and in our own neighborhoods. These are living, breathing documents whose meaning and interpretation are discussed constantly. The concepts of self-government -where elected officials are entrusted to represent the will of the people and a public forum where ideas are freely debated and all voices are considered in decision making-were not new to our nation’s founders. The Greek and Roman civilizations developed early concepts of democracy, where people ruled themselves through elected officials rather than a king. In Europe, documents such as the Magna Carta and English Bill of Rights, gave people some guaranteed rights even under the monarchy. The American colonists experimented with self-government and democracy for more than 150 years before the Declaration of Independence was adopted. The colonists elected officials to represent them in colonial assemblies and enacted laws in town meetings in New England. Religious freedom began to evolve over time, as colonists moved away from government-sanctioned religion that was the norm in Europe. The colonists grew so accustomed to governing themselves that they began to reject attempts by the British monarchy and Parliament to rule them from across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence was adopted creating the United States of America. The document officially severed the American colonies’ ties with King George II and Great Britain. The new country would become a representative democracy that guaranteed individual rights. It’s important to note that the colonists who crafted these documents were those who held power at the time. In colonial America in the late 1700s, it was white, male landowners who had the most rights in society. The rights of women and slaves were limited by societal norms, so the freedoms embodied in the founding documents were not immediately extended to them. The struggle for women’s rights, freed slaves and others came much later in the nation’s history. Take a closer look at the wording in the Founding Documents. Were founders clear on which freedoms were most important to them? Which rights and freedoms outlined in the Bill of Rights do we still debate today? Declaration of Independence  The Declaration of Independence announced the separation of the 13 colonies from Great Britain and the establishment of the United States of America. The document firmly stated the colonists’ belief that government derives its power from the will of the people and plays a strong role in securing individual rights. The Declaration of Independence included a long list of grievances against King George of Britain, who they felt rejected any attempts by the colonists to govern themselves, built an intimidating military, interfered with commerce, and denied them rights such as trial by jury. Many of the grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence formed the base for the rights that are protected in the First Amendment and the entire Bill of Rights. back to top U.S. Constitution After the Revolutionary War and the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the founders needed a governing document to prepare for self-government free from the monarchy. Their first attempt at a Constitution was the Articles of Confederation. Ratified in 1781, the Articles of Confederation created strong government powers for the 13 original colonies with a weak central government. This government structure presented many problems for the new country, such as limited power to settle disputes between states and little structure for regulating commerce and taxes. With law and order beginning to unravel by 1786, many of the founders believed it was time to revise the Articles of Confederation.  At the suggestion of James Madison and John Tyler, Congress called for a Constitutional Convention made up of delegates from each state to discuss revisions to the Articles of Confederation. The group convened for the first time on May 14, 1787 in Independence Hall in Philadelphia. After months of grueling debate and compromise, the delegates approved the first draft of the Constitution on September 17, 1787. The Constitution still needed to be ratified by nine states to officially go into effect forming the new federal government. The tension between individual rights and government powers were central to the discussion the founders had over the Constitution during the Constitutional Convention. This continued in the months that followed as the delegates and the public debated the merits of the Constitution and whether it should be ratified. The Anti-Federalists in particular were adamant that the Constitution needed amendments guaranteeing individual rights. Several states shared this view and only agreed to ratify the Constitution with the promise that a bill of rights would be added immediately. The U.S. Constitution created a central government that balances power between the federal government and states; a separation of powers within the government; and a system of checks and balances. The Bill of Rights later solidified the importance of individual rights, including the Tenth Amendment which said that any rights not stated in the Constitution were reserved to the states. back to top Bill of Rights The first ten amendments to the Constitution became known as the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights addressed many of the grievances expressed in the Declaration of Independence. Some of the colonists still had fresh memories of tyranny under the British monarchy and wanted to ensure individual rights were protected in any founding documents. While the Constitution awaited ratification from the states, the Anti-Federalists led the charge to guarantee individual rights. They wrote fiery essays and spoke in public forums in their home states. The Federalists fired back with their own essays and rhetoric defending the Constitution and its ability to protect individual liberties. Eventually the Constitution was ratified in September 1787, with the promise that a bill of rights would be added to the document. Two years later, James Madison proposed 12 amendments in what we now know as the Bill of Rights. Congress approved the Bill of Rights in September 1789 and then it was sent to the states for ratification. On December 15, 1791 ten of the amendments received the required approval from three-fourths of states. Originally, the Bill of Rights only applied to protecting individual rights from the federal government. These protections were later extended to include state governments. The First Amendment formed the cornerstone of the Bill of Rights, guaranteeing our basic rights of speech, religion, press, assembly and petition. With these five freedoms enshrined in the top spot, the First Amendment provided the framework that guaranteed us the other rights that follow it. Today, the Bill of Rights has 27 amendments and over time people have lobbied to add even more. We still debate the meaning and limits of these freedoms today. back to top << Previous Section Next section >> |